Resetting Slums: The Dual Faces of Urban Development

The contrast is striking when one moves from the central district of Phnom Penh to the outskirts where the slums are situated—it's like entering a parallel universe.

Reflecting on Cambodia's recent history, during the notorious Khmer Rouge regime, it was a place of immense suffering, estimated to have claimed the lives of two million people. After the end of the civil war, Cambodia gradually began rebuilding and embracing capitalism, resulting in significant economic growth since the 1990s. With economic growth, cities like Phnom Penh developed rapidly, doubling in population over the past 20 years.

The gleaming cities attracted many from rural provinces, not only seeking a better quality of life but also aspiring to find opportunities for prosperity. However, the limited job opportunities in the city, unable to absorb a large workforce in a short time, coupled with rents beyond the imagination of these people, left many struggling. Consequently, numerous residents find themselves living in rudimentary structures on the outskirts of the city, contributing to nearly 300 slums in Phnom Penh. The children and families living in these slums face extreme poverty, and the harsh living conditions sharply contrast with the prosperity of the city center, depicting the stark inequality and wealth disparity.

In 2015, Taiwan Fund for Children and Families (TFCF) established a direct service point in Cambodia, focusing on serving the urban slums, with one such service community being Andong, about 20 minutes from the Phnom Penh airport. The history of Andong dates back to 2006 when the government chose the Sambok Chap slum in the city center for planned development and relocation. Thousands of families were forced to move to their current location. Initially, the area was almost barren, lacking housing, water, electricity, sewage systems, flood prevention drainage, waste disposal, and basic infrastructure like schools or hospitals. Some residents lost their jobs and businesses due to the relocation. Residents engaged in small businesses, such as fruit stalls, had to start anew. Those working as construction workers had to incur high commuting costs, traveling at least 24 kilometers daily to reach the construction sites.

With the government continuously promoting urban development projects, policies for the forced eviction of slums have become common in recent years. Urban development has reclaimed space, leaving the poor without their homes. In Cambodia, this situation is prevalent, with most slum dwellers lacking land ownership or usage rights. Some lost relevant documents or proof of land ownership or residency during past conflicts, making it challenging to prove ownership.

In the post-urban renewal Phnom Penh, there are now rows of villas blending Khmer and European styles, equipped with various public facilities, presenting a stark contrast to the slums. The people forcibly relocated to other areas continue to see their rights to survival and housing justice compressed, escalating social conflicts.

Andong community has six communes, each with varying living conditions. Commune 1 has benefited from the investment of international and non-profit organizations, resulting in significant improvements in living conditions. However, compared to Commune 1, other areas just a street away remain sandy and muddy, especially during the rainy season.

In recent years, TFCF has expanded its services in the Andong community. Not only plan long-term programs based on sustainable thinking but also actively empower residents, encouraging them to participate voluntarily in community affairs, striving together to improve the community environment. With the easing of the pandemic this year, TFCF re-initiated its collaboration with National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University, jointly promoting the "Dream Base Project" starting from the Andong community.

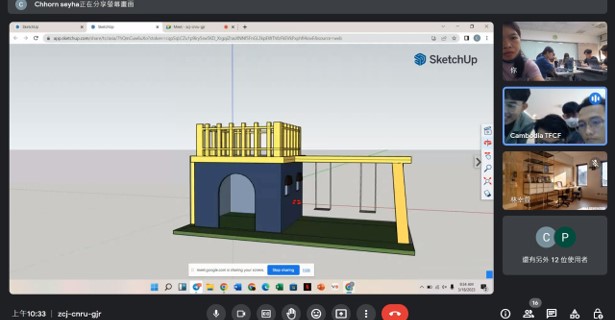

Since February, Professor Xu Beixian (currently an associate professor in the School of Architecture at the university) led several workshops, arranging for student volunteers to participate in the Youth Capacity Building program designed by TFCF to assist the youth. In the program activities, student volunteers and TFCF’s youth brainstormed ideas for families, communities, and community bases. Using the 3D design software SketchUp, they portrayed their dream homes and community bases.

The initiation, design, and operation of this project embody the spirit of participatory action. The aim is not only unilateral, top-down giving or imagination but rather a people-centric approach, collaboratively generating effective action plans in response to local needs. In the discussions, the TFCF’s youth, considering personal experiences and community perspectives, proposed adding balconies and swings to the imagined community base to address the lack of safe play spaces in the community.

Throughout the workshop process, we witnessed the grassroots power and resilience in Cambodian youth and deeply felt that international aid is not confined to tangible resource delivery. It can gradually empower local communities through the construction of soft power, shaping unique development models and community strength.

In the end, colleagues from TFCF and partners from National Yang-Ming Chiao Tung University recognized a meaningful conclusion: "While, in reality, most decisions come from donor organizations or government-funded stakeholders, to truly implement the concept of local participation, both bottom-up and top-down participation must proceed simultaneously." The most critical challenge is establishing participatory working methods on an innovative basis to genuinely achieve visions of sustainability, multi-participation, and rational co-construction.

Returning to the issue of Cambodia's urban slums, in our joint participation, stimulation, and implementation processes, we see another possibility unfold.